Snow to spring water in Japan the 100 Famous Waters

Japan’s mountains and deep winter snow make clear spring water. Snow and rain soak into the ground, move slowly through soil and rock, pick up minerals, and re-emerge at springs you can visit on foot. Simple. Good.

What is the “100 Famous Waters”?

Japan’s Ministry of the Environment has two official sets:

1985: the original 100

2008: another 100, added in the Heisei era

There’s no overlap. Together they make 200 celebrated water sites. The lists recognise quality and conservation, but being selected does not guarantee the water is safe to drink. Always follow the sign at the spot or check local city guidance.

Is the water clean enough to drink?

Sometimes yes — but never assume. Some springs are marked for drinking with a basin or tap. Others are for viewing only. The ministry states clearly: selection does not equal potability.

Is it snowmelt or groundwater?

Both. On the Japan Sea side, cold winter air from Siberia crosses the sea, builds snow clouds, and drops heavy snow on the ranges. That snowpack is a natural reservoir that melts and seeps into the ground, feeding aquifers and springs through the year.

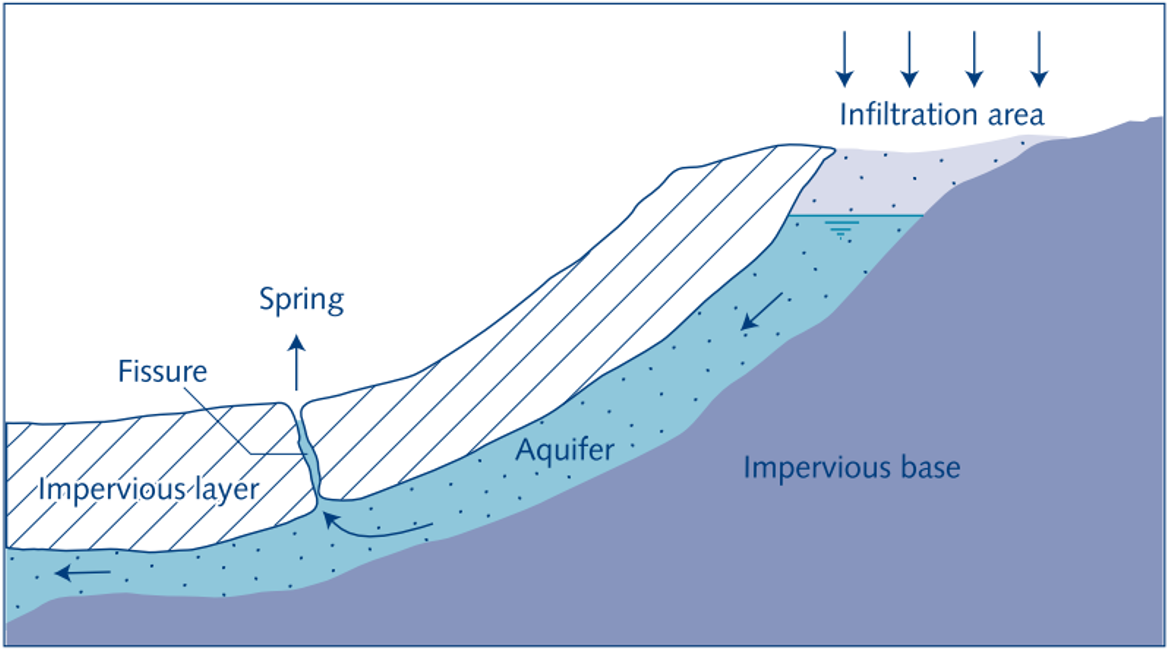

How does the filtration work?

As water percolates downward, soil and rock act as a natural filter. In volcanic regions like Mount Fuji, porous lava flows act like a sponge, routing water underground for years before it reappears at the surface. The result: clear, mineral-rich springs.

Where should I try this on a hike?

A few famous, easy-to-pair picks. All are on the official lists and close to walking routes or mountain days.

Oshino Hakkai, Yamanashi

Eight spring-fed ponds on Fuji’s north side. National Natural Monument and part of the Fuji World Heritage listing. The water you see started as precipitation on Fuji and moved through lava layers before surfacing here. Note: look for designated tasting points rather than drinking straight from the ponds.Kakita River Springs, Shizuoka

A short, spring-born river with remarkably stable temperature around 15°C year-round. Fed by Fuji’s groundwater. There’s a walkway, viewing platforms, and a water-filling spot nearby.Fukidashi Park Spring, Kyōgoku, Hokkaidō

Yōtei’s snow and rain become a powerful spring here: about 80,000 tons per day, at roughly 6.5°C all year. Local guidance asks you to boil raw water before use. Fun stop on a Yōtei loop day.Shirakawa Suigen, Kumamoto

Crystal spring at the foot of Aso. About 60 tons per minute at around 14°C. Used locally for drinking and for brewing. Easy to visit between hikes on Aso’s trails and caldera rims.Azumino Wasabi Field Springs, Nagano

North Alps snowmelt becomes huge clear springs at the fan-edge of the valley. Around 700,000 tons per day, rarely above 15°C even in midsummer. Flat paths, mountain views, and lots of water culture to see.

Quick etiquette

Use a clean bottle

Don’t touch the spout

If the sign doesn’t say “drinking,” don’t risk it

Why talk about snow here?

Because the snowpack is the source. In the heavy snow belt, totals often exceed 6m / 20ft at town level and more than 14m / 46ft in the mountains. That’s what powers the springs months later. If you want to see the snow itself, not just the water it creates, join one of my winter trips. That’s where you see how Japan’s snow shapes landscapes, trails, and daily life.

And if you’re here in the green season, explore a few springs along your hikes — or read more about countryside living and property on my other blogs!

Reference:

The 100 Famous Waters list from 1985

Hokkaido: Yotei no Fukidashi Yusui, Kanro Sensui, Naibetsugawa Yusui

Aomori: Tomita no Shitsuko, Igami no Shitsuko

Iwate: Water of Ryusendo, Kanazawa Shimizu

Miyagi: Katsuraha Shimizu, Hirose River

Akita: Rokugo Yusui group, Chikara Mizu

Yamagata: Gassan foothill springs, Omigawa

Fukushima: Bandai west foothill springs, Onogawa springs

Ibaraki: Yamizo River springs

Tochigi: Izuruhara Benten Pond spring, Shojinzawa spring

Gunma: Ogawa weir, Hakoshima springs

Saitama: Fuppu River and Yamato water

Chiba: Yuya no Shimizu

Tokyo: Otaka no Michi and Masugata Pond springs, Mitake mountain torrent

Kanagawa: Hadano Basin spring group, Shasui Falls and Takizawa River

Niigata: Ryugakubo water, Todo no Mori springs

Toyama: Kurobe fan springs, Anantan no Reisui, Tateyama Tamadono springs, Uriwari no Shozu

Ishikawa: Kobo Pond water, Kowa fine water, Mitarai Pond

Fukui: Uriwari no Taki, Oshozu, Unose

Yamanashi: Oshino Hakkai, Yatsugatake south-slope springs, Hakushu and Ojira River

Nagano: Sarukura spring, Azumino wasabi field springs, Hime River source springs

Gifu: Sogi sui, Nagara River midstream, Yoro Falls and Kikusui spring

Shizuoka: Kakita River springs

Aichi: Kiso River midstream

Mie: Chishaku irrigation, Erihara water cave

Shiga: Juo village water, Izumi Shrine spring

Kyoto: Fushimi aroma water, Iso Shimizu

Osaka: Rikyu no Mizu

Hyogo: Miyamizu, Nunohiki mountain torrent, Chigusa River

Nara: Dorogawa spring group

Wakayama: Nonaka no Shimizu, Kimiidera three wells

Tottori: Ama no Manai

Shimane: Tengawa no Mizu, Dangyo waterfall spring

Okayama: Shiogama cold spring, Omachi cold spring, Iwai

Hiroshima: Ota River midstream, Deai Shimizu

Yamaguchi: Beppu Benten Pond spring, Sakura Well, Jakuji River

okushima: Egawa springs, Tsurugi-san sacred water

Kagawa: Yubune no Mizu

Ehime: Uchinuki, Jo no Fuchi, Kannon sui

Kochi: Shimanto River, Antoku sui

Fukuoka: Kiyomizu spring, Furo sui

Saga: Ryumon clear water, Kiyomizu River

Nagasaki: Shimabara spring group, Todoroki torrent

Kumamoto: Todoroki spring source, Shirakawa spring source, Kikuchi water source, Ikeyama spring source

Oita: Oike Pond springs, Taketa spring group, Hakusan River

Miyazaki: Idenoyama springs, Aya River spring group

Kagoshima: Yakushima Miyanoura dake stream, Kirishima Maruike spring, Kiyomizu spring

Okinawa: Kakinohana Hi-ja spring